Data Exploration Using Spark¶

Today, we'll learn how to use Spark, a framework for large-scale data processing. All of the frameworks that we've used so far (e.g., Pandas, R) are designed to be run on a single computer. However, many data sets today are too large to be stored on a single computer. Even when a dataset can be stored on one computer, the data set can often be processed much more quickly using multiple computers. Spark is designed for this purpose: it allows you to concisely describe a program to analyze data on many computers, and hides many of the details of coordinating data analysis on many machines.

If you have problems during the tutorial, checkout the FAQ at the bottom of this page.

Don't forget to fill out the response quiz on BCourses.

Table of Contents¶

Getting Started: How to start a Spark application

Distributed Data: How data is stored in-memory across a cluster using Spark

Spark Operations: An introduction to Spark functionality

Basic operations: How to inspect data you have stored in Spark

Data parallel operations: Transforming Spark datasets with operations that are easily parallelized

Parallelism: Understanding the importance of the number of data partitions and tasks in a Spark job

Multi-stage operations: More complicated functionality that requires multiple stages of tasks

Aggregations: How to aggregate all of the entries in a particular RDD

Joins: How to perform Joins with Spark

Getting Started¶

Spark is already installed on your amazon 2 instance. The data for this assignment is also on your disk, but for mysterious reasons isnt readable. To fix that do:

cd /data/MovieLens

chmod 644 *

To start Spark's Python wrapper, just do:

cd /opt/spark/bin

./pyspark

To work directly with Spark in its native Scala, you would replace "pyspark" with "spark-shell" above.

A key concept with Spark is the SparkContext. The SparkContext captures information about how Spark is run, whether single-node or in cluster mode. In both Scala and Python, the SparkContext is held in the variable "sc". You will see many Spark commands invoked as methods on the SparkContext.

Distributed Data¶

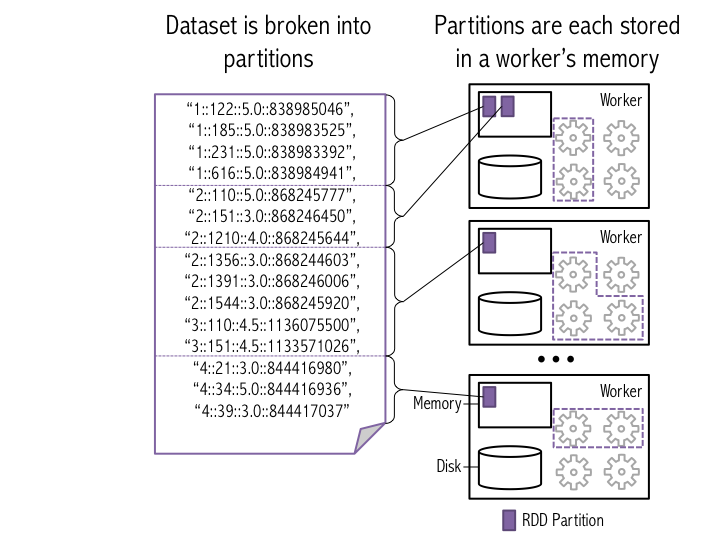

In this class, when we have analyzed data, we have typically represented a dataset as a list of entries. In Spark, datasets are also represented as a list of entries; the key difference is that now the list is broken up into many different partitions that are each stored on a different machine. Each partition holds a unique subset of the entries in the list. Spark calls data sets that it stores "Resilient Distributed Datasets" (RDDs).

One of the defining features of Spark compared to other data analytics frameworks (like Hadoop, which many of you used in CS61C) is that it stores data in memory rather than on disk. This allows Spark applications to run much more quickly, because they aren't slowed by needing to read data from disk. Let's load some data for our Spark application to use.

The figure below illustrates how Spark breaks a list of data entries into partitions that are each stored in memory on a worker.

To load the data, we'll use sc.textFile(), which tells Spark create a new set of input data based on data read from a given input file path (in this case, movielens/large/ratings.dat). In this case, the input file path points to a file in Hadoop Distributed File System (HDFS); HDFS stores the data on the disks of machines in the cluster. The second argument to sc.textFile() tells Spark how many partitions to break the data into when it stores the data in memory (we'll talk more about this later in the tutorial). Next, we call cache() on the new dataset to signal to Spark that this data should be kept in memory (for faster access in the future).

# The first argument to textFile is a path to the data in HDFS.

# The second argument specifies how many pieces to break the file

# into; we'll talk more about this later in the tutorial.

raw_ratings = sc.textFile("/data/MovieLens/ratings.dat", 10)

# Give our RDD a name so it's easily identifiable in the UI.

raw_ratings.setName("raw ratings")

raw_ratings.cache()

That was fast! But actually too fast. Remember we talked about a feature of Spark called "lazy evaluation": Spark only computes a dataset or a transformation on a dataset when it's necessary to return a result. Here, we haven't asked for any results from the raw_ratings dataset, so Spark avoids unnecessary work by not reading in the dataset yet. To force Spark to read in the raw_ratings data, we'll count the entries in the dataset. count() requires the dataset to compute its result, so now Spark will read the data from HDFS.

entries = raw_ratings.count()

print "%s entries in ratings" % entries

One thing that's useful when we have a new dataset is to look at the first few entries to get a sense of what the data looks like. In Spark, we do that using the take() command (analogous to the head() command in Pandas). The format of each entry is UserID::MovieID::Rating::Timestamp.

# Look at the first 10 items in the dataset.

raw_ratings.take(10)

Spark Operations¶

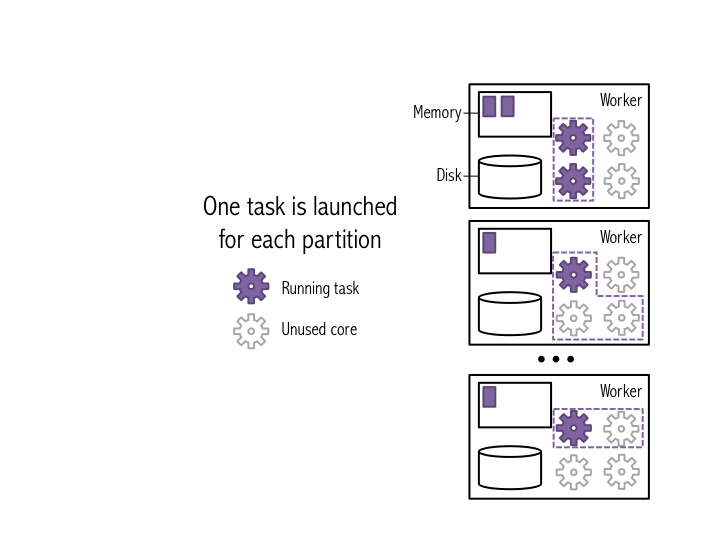

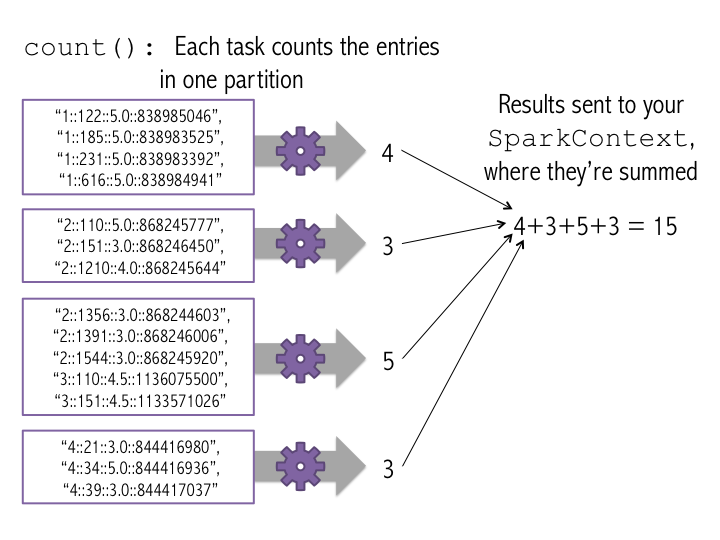

So far, we've created a distributed dataset that's split into many partitions that are each stored on a single machine in our cluster. Let's look at what happens when we do a basic operation on the dataset. One of the most basic jobs that we can run is the count() job that we ran earlier. When you run count() on a dataset, a single stage of tasks is launched. A stage is a group of tasks that all perform the same computation, but on different input data. One task is launched for each partitition, as shown in the example below. A task is a unit of execution that runs on a single machine. In this example, the dataset is broken into 4 partitions, so 4 count() tasks are launched.

Each task counts the entries in its partition and sends the result to your SparkContext, which adds up all of the counts, as shown in the figure below.

The above figures showed what would happen if we ran count() on a small example dataset with just 4 partitions.

Count all of the entries in the ratings dataset again. How long did your new count() stage take? How long did the old stage take? Can you explain the difference?

raw_ratings.count()

Data Parallel Operations¶

Many useful data analysis operations can be specified as "do something to each item in the data set". These data-parallel operations are convenient because each item in the dataset can be processed individually: the operation on one entry doesn't effect the operations on any of the other entries. Therefore, Spark can easily parallelize the operation: each task does the "something" to it's own partition of the dataset. map(f) is one such example: it applies a function f to each item in the dataset, and outputs the resulting dataset. When we run map(f) with Spark, each task applies f to all of the entries in a particular partition, and outputs a new partition. We'll use map(f) to convert the ratings dataset to a format that's a little easier to manipulate. Having "::"-separated strings for each data item is not very convenient; let's convert the input data into tuples: (UserID, MovieID, Rating, Timestamp), and convert the IDs, ratings, and timestamps to appropriate data types. The figure below shows how this would work on the smaller data set from the earlier figures. Note that one task is launched for each partition.

def get_tuple(entry):

items = entry.split("::")

return int(items[0]), int(items[1]), float(items[2]), int(items[3])

ratings = raw_ratings.map(get_tuple)

# Set the name of the new RDD, like we did before, so that it's easily

# identifiable in the UI.

ratings.setName("ratings")

ratings.take(10)

Unless you explicitly ask Spark to save a dataset, it won't keep it in memory; instead, the ratings variable stores how to recompute ratings if you use it again. We'll be using ratings a bunch more time so we want to keep it in memory for quick access, and drop the older raw_ratings dataset to clear up space.

# Cache ratings in memory and call count() to force Spark to bring it into memory.

ratings.cache()

ratings.count()

# Remove raw_ratings from memory, since we don't need it anymore.

raw_ratings.unpersist()

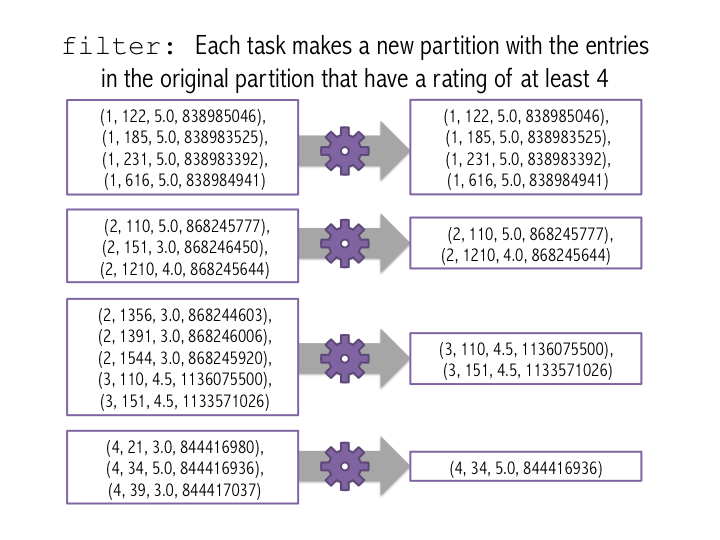

Another data-parallel operation is filter(f). Filter takes a function f that should take an entry and return True if the entry should be in the new dataset. filter(f) returns a new RDD composed of all of the entries of the original datset for which f() returns True. Like map(), filter can be applied indivudually to each entry in the dataset, so is easily parallelized using Spark. The movie ratings are between 0 and 5; let's count how many movies had a rating of at least 4. The figure below shows how this would work on the small 4-partition dataset.

# First, create a new RDD make up of the entries of new_ratings

# that had a rating of at least 4.

count = ratings.filter(lambda x: x[2] >= 4).count()

print "%s entries have ratings of at least 4" % count

DIY¶

How many ratings did user 1 submit?

### YOUR CODE HERE

What fraction of ratings are 5?

### YOUR CODE HERE

Multi-stage Jobs¶

So far, we've focused on simple, data-parallel operations, where we have a single stage of tasks. A stage is a group of tasks that all do the same thing, but to different partitions of the dataset. Many types of data analysis require multiple stages of tasks. As an example of such an operation, let's count the number of entries with each rating value.

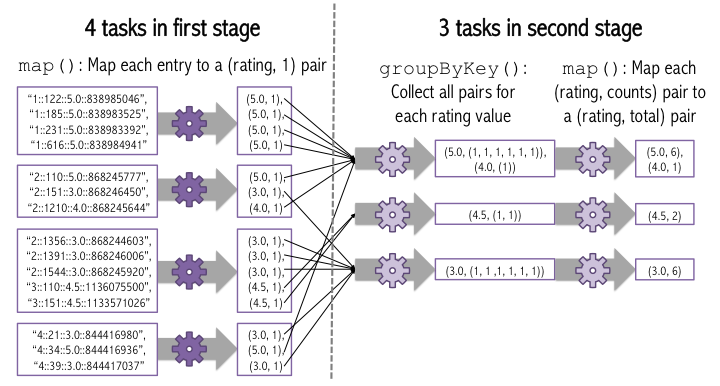

The basic idea of how this will work is that first, we do a data-parallel operation where for a particular entry, we return the number of entries with each rating value. So, for each entry, we'll return (rating, 1), where rating is the rating in the entry. Now, each task has a bunch of (rating, 1) pairs, for different ratings, so the counts for a particular rating (e.g., for rating 5) are spread across a bunch of different tasks on different machines. We need to aggregate the counts for each rating. We'll do this using a "shuffle", where all of the counts for a particular rating get sent to a single machine that can aggregate them. The figure below shows how this will work.

To write this computation in Spark, we first do a map(), similar to what we did earlier, to get the (rating, 1) pairs. Then, we use groupByKey() to group all of the pairs for a singe rating. groupByKey() returns a list of (key, values) pairs, where values is a list of values for that key. Finally, we call map() to add up all of the values for each key. Note that the Spark transformation operations (e.g., map(), groupByKey(), filter()) all return a new RDD, so they can be chained together, as we do in the example below.

def add_counts(entry):

rating = entry[0]

counts = entry[1]

return (rating, sum(counts))

rating_counts = ratings.map(lambda x: (x[2], 1))

aggregated_counts_rdd = rating_counts.groupByKey().map(add_counts)

print aggregated_counts_rdd

Remember that Spark uses lazy evaluation: since we haven't asked Spark to do anything with the aggregated_counts_rdd dataset, it hasn't computed it yet. Spark has just created a RDD object that stores how to compute aggregated_counts_rdd if we need it in the future. In this case, the resulting aggregated_counts_rdd dataset will be small, so we want to just return the dataset as a Python list. We can do this using the collect() function, which is like take(x) except that it returns the entire dataset rather than just the first x entries.

aggregated_counts_list = aggregated_counts_rdd.collect()

print aggregated_counts_list

We can use matplotlib to plot the results, similar to what we've done earlier in the class.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plot

# Magic command to make matplotlib and ipython play nicely together.

%matplotlib inline

width = 0.3

rating_values = [x[0] - width / 2 for x in aggregated_counts_list]

counts = [x[1] for x in aggregated_counts_list]

# The bar() function takes 2 lists: one list of x-coordinates of the left

# side of each bar, and one list of bar heights.

plot.bar(rating_values, counts, width)

DIY¶

We've done a lot of work on the ratings dataset. Now, it's time for you to do some processing a new dataset that stores information about each movie. The movie dataset is stored at /data/MovieLens/movies.dat and each entry is formatted as MovieID::Title::Genres. Read this dataset into memory and convert each entry to a tuple where the movie ID is an integer, the title is a String, and the genre is a list of strings. How many total movies are there? (response form)

### YOUR CODE HERE

count = # Count all of the entries in the movies dataset

print "Number of movies: ", count

How many movies are there for each genre? You may find it useful to use Spark's flatMap() function, which is like map() except that the provided function maps each input item maps to a list containing 0 or more output items (the FAQ includes more description of the flatMap() function). We've included a plot_bars() function for you that accepts a list of (genre_name, count) pairs and will make a bar graph.

def plot_bars(genre_counts):

""" genre_counts should be a list of (genre_name, count) pairs. """

x_coords = range(len(genre_counts))

genre_names = [x[0] for x in genre_counts]

counts = [x[1] for x in genre_counts]

width = 0.8

plot.bar(x_coords, counts, width)

plot.xlabel("Genre")

plot.ylabel("Number of Movies")

plot.xticks([x + width/2.0 for x in x_coords], genre_names, rotation='vertical')

### YOUR CODE HERE

So far, we've used groupByKey() when we want to combine all of the values for a particular key. Recall that groupByKey() collects all of the values for each key in one dataset. Then, we used a subsequent map() call to aggregate all of the values. However, this isn't very efficient; often, we don't need all of the values at once. Instead, we can often use incrementally reduce the set of values for each key. We do this by specifying a function f that takes two values and combines them, and calling reduceByKey(f) instead of groupByKey(). Spark keeps using f to combine pairs of values for the same key until there is only 1 value left for each key. Because Spark can incrementally combine pairs of values for a particular key, so that it never has to store all of the values for a key at one time. Let's use reduceByKey to more efficiently count the number of ratings with each ratings value.

# The function you give to reduceByKey should take two values and produce

# a new value. Note that the datatype of the two input values and the output

# value need to be the same.

def add_two_counts(count1, count2):

return count1 + count2

rating_counts = ratings.map(lambda x: (x[2], 1))

aggregated_counts_rdd = rating_counts.reduceByKey(add_two_counts)

print aggregated_counts_rdd.collect()

This dataset is not large enough to notice a significant time improvement between the two implementations, but it can make a big difference for larger datasets. Use reduceByKey to write your code to count the number of movies for each genre more efficiently.

### YOUR CODE HERE

Aggregations¶

We have already seen a two ways to aggregate all of the entries in a particular dataset: count(), which counts all of the entries, and collect(), which returns the entire RDD as a Python list. One more useful function for aggregating data in a particular dataset is the reduce function. reduce works similarly to reduceByKey: it takes a function f and uses that function to incrementally combine values. The difference between reduce and reduceByKey is that reduce combines all of the entries in a particular dataset -- not just the entries for a particular key. reduce will return a single value, whereas reduceByKey returns a new RDD with one entry for each key. Let's use reduce to compute the average rating.

ratings_total = ratings.map(lambda x: x[2]).reduce(lambda x, y: x + y)

average_rating = ratings_total * 1.0 / ratings.count()

print "Average rating:", average_rating

DIY¶

Use reduce to count the average number of genres that a movie is classified into.

### YOUR CODE HERE

Joins¶

Spark also supports joins. Joins operate on two data sets, where the entries in each dataset are (key, value) pairs. d1.join(d2) returns all pairs (k, (v1, v2)) such that (k, v1) was in d1 and (k, v2) was in d2. As an example of a join, let's compute the number of times that each movie was rated. First, we'll compute the number of times that each movie was rated using the ratings dataset, and then we'll use a join to get the movie names from the movies dataset.

# YOUR CODE HERE: Create a dataset of (movieID, number of ratings pairs)

rating_count_per_movie = # YOUR CODE HERE

# Now join ratings_per_movie with moives to get a dataset with movie names and the number of rating

rating_count_per_movie_with_names = movies.map(lambda x: (x[0], x[1])).join(ratings_per_movie)

rating_count_per_movie_with_names.take(10)

DIY¶

Which 10 movies have the most ratings? You may want to use the sortByKey() function, which expects to be called on an RDD composed of (key, value) pairs and sorts them by key. sortByKey() takes an optional parameter describing whether the keys should be sorted in ascending order.

### YOUR CODE HERE.

Gosh these movies are old! Make a bar chart showing the number of movies for each year. You'll need to parse the year out of the movie title.

### YOUR CODE HERE

Of movies with at least 100 ratings, which 10 have the lowest average ratings?

### YOUR CODE HERE

Frequently Asked Questions¶

What are all of the operations I can do on a Spark dataset (RDD)?¶

This Page lists all of the operations you can do on a Spark RDD. Spark also has a Scala API (Scala is a programming language similar to Java); the documentation for the Scala functions is sometimes more helpful, and the Python functions work in the same way.

How do I use matplotlib?¶

There are lots of good examples on the matplotlib website. For example, this page shows how to plot a single line.

Why am I getting an OutOfMemoryError?¶

If you get an error that looks like: org.apache.spark.SparkException: Job aborted: Exception while deserializing and fetching task: java.lang.OutOfMemoryError: Java heap space, it probably means that you've tried to collect too much data on the machine where Python is running. This is likely to happen if you do collect() on a large dataset. The best way to remedy this problem is to restart your iPython notebook (go to the main server, at port 8888 of the machine you were assigned, click "Shutdown" on your notebook, and then open it again) and don't do collect() on a large dataset.

Curious why you're getting a Java error when your program is written in Python? Spark is mostly written in Java (and Scala, a language built on top of Java). We're using pyspark here, which uses a translation layer to translate between Python and Java. Your Python SparkContext object is backed by a Java SparkContext object; all operations you run on Spark datasets are passsed through this Java object. So, if you try to collect a result that's too large, the Java Virtual Machine that's running the Java SparkContext runs out of memory.

Python / Spark is giving me a crazy weird error!¶

Spark is mostly written in Scala and Java, and the Python version of the code ("pyspark") hooks into the Java implementation in a way that can make error messages very difficult to understand. If you get a hard-to-understand error when you run a Spark operation, we recommend first narrowing down the error so that you know exactly which operation caused the error. For example, if rdd.groupByKey().map(lambda x: x[1]) fails with an error, separate the groupByKey() and map() calls onto separate lines so you know which one is causing the error. Next, double check the function signature to make sure you're passing the right arguments. Pyspark can fail with a weird error if a RDD operation is given the wrong number or type of arguments. If you're still stumped, try using take(10) to print out the first 10 entries in the dataset you're calling the RDD operation on. Make sure the function you're calling and the arguments you're passing in make sense given the format of the input dataset.

Can you explain more about how flatMap() works?¶

Let's look at an example: suppose you have an RDD where each entry lines of text in a book, and you want to make a new RDD where each entry is a single word. You could use flatMap() to do this as follows:

lines_in_book = [

"I am Sam",

"I am Sam",

"Sam I am",

"Do you like",

"green eggs and ham?"]

# sc.parallelize turns a Python list into an RDD.

lines_in_book_rdd = sc.parallelize(lines_in_book)

# Notice that here, the function passed to flat map will return a list.

words_rdd = lines_in_book_rdd.flatMap(lambda x: x.split(" "))

print words_rdd.collect()

The resulting RDD will have a list of words. The function we passed into flatMap returned a list of words for each entry in the original RDD, and flatMap combines all of these lists of words into a single list. Let's do this same thing with map to see what's different.

list_of_words_rdd = lines_in_book_rdd.map(lambda x: x.split(" "))

print list_of_words_rdd.collect()

Notice that now the resulting RDD has a list of lists.

Another way to think about this is that map() always returns a new RDD with the same number of entries as the original RDD: each entry in the original RDD is mapped to one entry in the new RDD. With flatMap(), each entry in the original RDD maps to a list of 0 or more entries, so the new RDD isn't necessarily the same size as the old RDD (it might be larger or smaller).

Lab Responses¶

Don't forget to fill out the response quiz on BCourses.