Plotting¶

Use matplotlib, pandas, and plotly to leverage Python's power of data visualization.

Tools (Packages) for Plotting with Python¶

Several packages enable plotting in Python. The last page already introduced NumPy and pandas for plotting histograms. pandas plotting capacities go way beyond just plotting histograms and it relies on the powerful matplotlib library. SciPy's matplotlib is the most popular plotting library in Python (since its introduction in 2003) and not only pandas, but also other libraries (for example the abstraction layer Seaborn) use matplotlib with facilitated commands. This page introduces the following packages for data visualization:

- matplotlib - the baseline for data visualization in Python

- pandas - as wrapper API of matplotlib, with many simplified options for meaningful plots

- plotly - for interactive plots, in which users can change and move plot scales

Matplotlib¶

Because of its complexity and the fact that all important functions can be used with pandas in a much more manageable way, we will discuss matplotlib only briefly here. Yet it is important to know how matplotlib works to better understand the baseline of plotting with Python and to use more complex graphics or more plotting options when needed.

In 2003, the development of matplotlib was initiated in the field of neurobiology by John D. Hunter (†) to emulate The MathWork's MATLAB® software. This early development constituted the pylab package, which is deprecated today for its bad practice of overwriting Python (in particular NumPy) plot() and array() methods/objects. Today, it is recommended to use:

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt.

Some Terms and Definitions¶

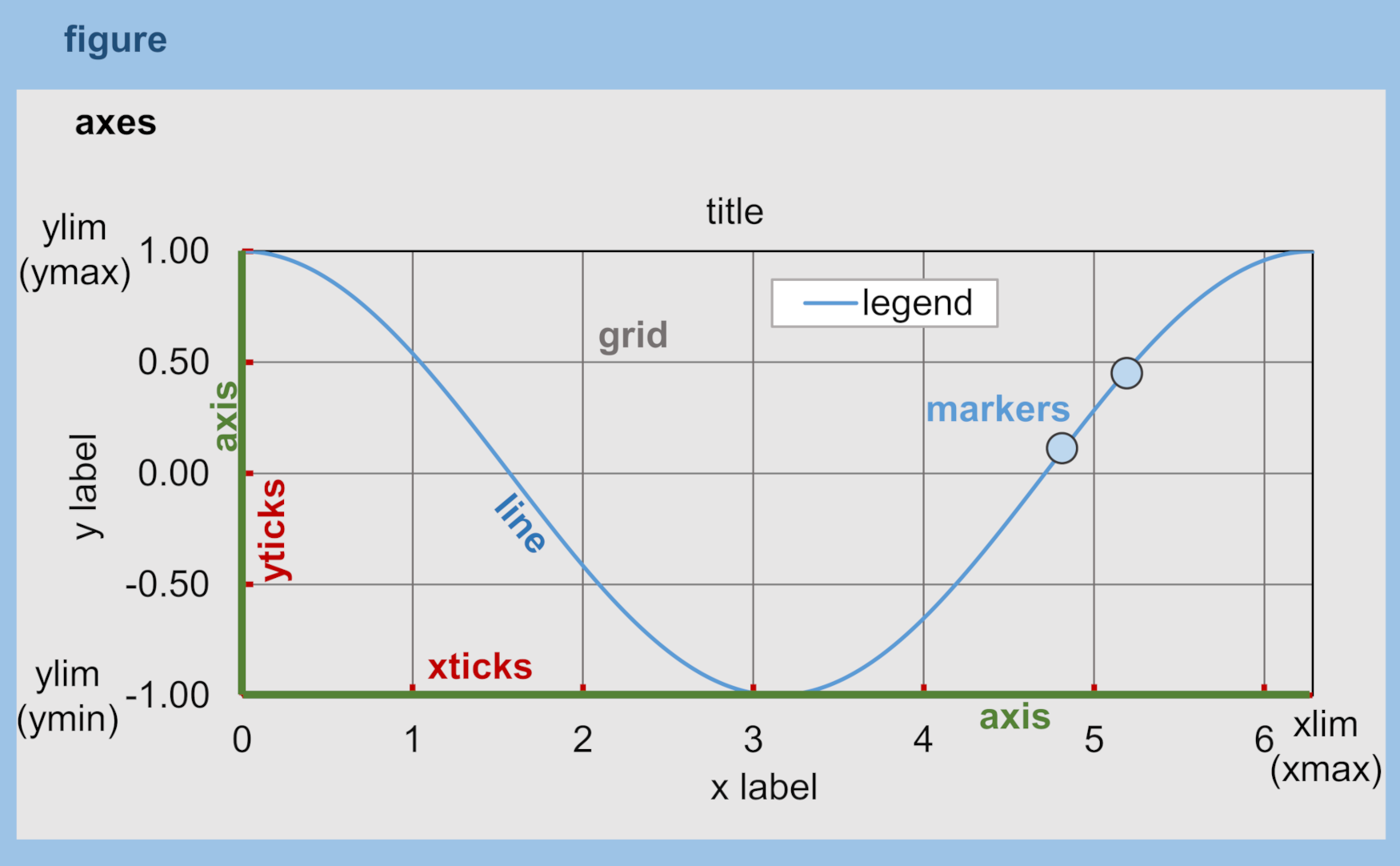

A plt.figure can be thought of as a box containing one or more axes, which represent the actual plots. Within the axes, there are smaller objects in the hierarchy such as markers, lines, legends, and text fields. Almost every element of a plot is a manipulable attribute and the most important attributes are shown in the following figure. More attributes can be found in the showcases of matplotlib.org.

Step-by-step Recipe for 1d/2d (line) Plots¶

- Import matplolib's

pyplotpackage withimport matplotlib.pyplot as plt - Create a figure with

plt.figure(figsize=(width_inch, height_inch), dpi=int, facecolor=str, edgecolor=str) - Add axes to the figure with `axes=fig.add_subplot(row=int, column=int, index=int, label=str)

- Generate a color map;

plt.cm.getcmap()generates an array of colors as explained in the NumPy section. For examplecolormap=([255, 0, 0])creates a color map with just one color (red). - To plot the data with

- lines use

axes.plot(x, y, linestyle=str, marker=str, color=Colormap(int), label=str)and many more**kwargscan be defined (go the matplotlib docs). - points (markers) use

axes.scatter(x, y, MarkerStyle=str, cmap=Colormap, label=str)and many more**kwargscan be defined (go the matplotlib docs)

- lines use

- Manipulate axis ticks

plt.xticks(list)define x-axis ticksplt.yticks(list)define y-axis ticksaxes.set_xlim(tuple(min, max))sets the x-axis minimum and maximumaxes.set_ylim(tuple(min, max))sets the y-axis minimum and maximumaxes.set_xlabel(str)sets the x-axis labelaxes.set_ylabel(str)sets the y-axis label

- Add a legend (optionally) with

axes.legend(loc=str, facecolor=str, edgecolor=str, framealpha=float_between_0_and_1)and many more**kwargscan be defined (confer to the matplotlib docs). - Optional: Save the figure with

plt.savefig(fname=str, dpi=int)with many more**kwargsavailable (confer to the matplotlib docs).

Tip: Most of the below illustrated

matplotlibfeatures are embedded in a plotter script, which is available at a supplemental repository of the hydro-informatics.com eBook.

The following code block illustrates a plot recipe using randomly drawn samples from a Weibull distribution with the distribution shape factor a (for a=1, the Weibull distribution reduces to an exponential distribution). The seed argument describes the source of randomness and seed=None makes Python use randomness from operating system variables.

The code block defines a function called plot_xy that requires x and y arguments and accepts the following optional keyword arguments:

plot_type=strdefines if a line or scatter plot should be produced,label=strsets the legend,save=strdefines a path where the figure should be saved (the figure is not saved if nothing is provided). To activate saving a figure, use the optional keyword argumentsave, for example,save='C:/temp/weibull.png'saves the figure to a localtempfolder on a WindowsC:drive.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import matplotlib.cm as cm

import numpy as np

x = np.arange(1, 100)

y = np.random.RandomState(seed=None).weibull(3., x.__len__())

def plot_xy(x, y, plot_type="1D-line", label="Rnd. Weibull", save=None):

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(6.18, 3.82), dpi=100, facecolor='w', edgecolor='gray') # figsize in inches

axes = fig.add_subplot(1, 1, 1, label=label) # row, column, index, label

colormap = cm.plasma(np.linspace(0, 1, len(y))) # more colormaps: http://matplotlib.org/users/colormaps.html

if plot_type == "1D-line":

ax = axes.plot(x, y, linestyle="-", marker="o", color=colormap[0], label=label) # play with the colormap index

if plot_type == "scatter":

ax = axes.scatter(x, y, marker="x", color=colormap, label=label)

if not "ax" in locals():

print("ERROR: No valid input data provided.")

return -1

plt.xticks(list(np.arange(0, x.__len__() + 10, (x.__len__() + 1) / 5.)))

plt.yticks(list(np.arange(0, np.ceil(y.max()), 0.5)))

axes.set_xlim((0,100))

axes.set_ylim((0,2))

axes.set_xlabel("Linear x data")

axes.set_ylabel("Scale of " + str(label))

axes.legend(loc='upper right', facecolor='y', edgecolor='k', framealpha=0.5)

if save:

plt.savefig(save)

print("Plot lines")

plot_xy(x, y)

print("Scatter plot")

plot_xy(x, y, plot_type="scatter", label="Rand. Weibull scattered")

Challenge: The

plot_xyfunction has some weaknesses. For instance, if more arguments are provided, orydata is a multidimensional array (not nx1 or 1xm) that should produce multiple plot lines, the function will not work. So, how can you optimize theplot_xyfunction, to make it more robust and enable multi-line plotting?

Surface and Contour Plots¶

matplotlib provides multiple options to plot X-Y-Z (2d/3d) data such as:

- Surface plots with color shades:

axes.plot_surface(X, Y, Z) - Contour plots:

axes.contour(X, Y, Z) - Contour plots with filled surfaces:

axes.contourf(X, Y, Z) - Surface plots with triangulated mesh:

axes.plot_trisurf(X, Y, Z) - Three-dimensional scatter plots:

axes.scatter3D(X, Y, Z) - Streamplots (e.g., of velocity vectors):

axes.streamplot(X, Y, U, V) - Color-coded representation of gridded values with (annotated) heatmaps (e.g., for habitat suitability index maps):

axes.imshow(data, **kwargs)

This section features the usage of streamplots, which are a useful tool for the visualization of velocity vectors (flow fields) in rivers (e.g., produced with a numerical model). To generate a streamplot:

- Create an

X-Ygrid, for example with the NumPy'smgridmethod:Y, X = np.mgrid[range, range] - Assign stream field data (can be artificially generated, for example, in the form of

UandVvariables in the below code block) to the grid nodes. Note that every grid node can only get assigned one scalar value, which isvelocity(as a function of the 2-directional field data) in the below code block. - Generate figures, as before in the

plot_xyfunction example (see the above 1d/2d plot instructions).

The below code block illustrates the generation of a streamplot (adapted from the matplotlib docs) and uses import matplotlib.gridspec to place the subplots in the figure.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import matplotlib.gridspec as gridspec

# generate grid

w = 100

Y, X = np.mgrid[-w:w:10j, -w:w:10j] # j creates complex numbers

# calculate U and V vector matrices on the grid

U = -2 - X**2 + Y

V = 0 + X - Y**2

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(6., 2.5), dpi=200)

fig_grid = gridspec.GridSpec(nrows=1, ncols=2)

velocity = np.sqrt(U**2 + V**2) # calculate velocity vector

# Varying line width along a streamline

axes1 = fig.add_subplot(fig_grid[0, 0])

axes1.streamplot(X, Y, U, V, density=0.6, color='b', linewidth=3*velocity/velocity.max())

axes1.set_title('Line width variation', fontfamily='Tahoma', fontsize=8, fontweight='bold')

# Varying color along a streamline

axes2 = fig.add_subplot(fig_grid[0, 1])

uv_stream = axes2.streamplot(X, Y, U, V, color=velocity, linewidth=2, cmap='Blues')

fig.colorbar(uv_stream.lines)

axes2.set_title('Color maps', fontfamily='Tahoma', fontsize=8, fontweight='bold')

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Fonts and Styles¶

The previous example featured a font type adjustment for the plot titles (axes.set_title('title', font ...)). The font and its characteristics (e.g., size, weight, style, or family) can be defined more coherently with matplotlib.font_manager.FontProperties (cf. the matplotlib docs), where plot font settings can be globally modified within a script.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from matplotlib.font_manager import FontProperties

from matplotlib import rc

# create FontProperties object and set font characteristics

font = FontProperties()

font.set_family("sans-serif")

font.set_name("Times New Roman")

font.set_style("italic")

font.set_weight("semibold")

font.set_size(10)

print("Needs to be converted to a dictionary: " + str(font))

# translate FontProperties to a dictionary

font_dict = {"family": "normal"}

for e in str(font).strip(":").split(":"):

if "=" in e:

font_dict.update({e.split("=")[0]: e.split("=")[1]})

# apply font properties to script

rc("font", **font_dict)

# make some plot data

x_lin = np.linspace(0.0, 10.0, 1000) # evenly spaced numbers over a specific interval (start, stop, number-of-elements)

y_osc = np.cos(5 * np.pi * x_lin) * np.exp(-x_lin)

# plot

fig, axes = plt.subplots(figsize=(6.18, 1.8), dpi=150)

axes.plot(x_lin, y_osc, label="Oscillations")

axes.legend()

axes.set_xlabel("Time (s)")

axes.set_ylabel("Oscillation (V)")

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Instead of using rc, font characteristics can also be updated with matplotlib's rcParams dictionary. In general, all font parameters can be accessed with rcParams along with many more parameters of plot layout options. The parametric options are stored in the matplotlibrc file and can be accessed with rcParams["matplotlibrc-parameter"]. Read more about modification options ("matplotlibrc-parameter") in the matplotlib docs. In order to modify a (font) style parameter use rcParams.update({parameter-name: parameter-value}) (which does not always work, for example, in jupyter).

In addition, many default plot styles are available through matplotlib.style with many style templates. The following example illustrates the application of rcParams and style variables to the previously generated x-y oscillation dataset.

from matplotlib import rcParams

from matplotlib import rcParamsDefault

from matplotlib import style

rcParams.update(rcParamsDefault) # reset parameters in case you run this block multiple times

print("Some available serif fonts: " + ", ".join(rcParams['font.serif'][0:5]))

print("Some available sans-serif fonts: " + ", ".join(rcParams['font.sans-serif'][0:5]))

print("Some available monospace fonts: " + ", ".join(rcParams['font.monospace'][0:5]))

print("Some available fantasy fonts: " + ", ".join(rcParams['font.fantasy'][0:5]))

# change rcParams

rcParams.update({'font.fantasy': 'Impact'}) # has no effect here!

print("Some available styles: " + ", ".join(style.available[0:5]))

style.use('seaborn-darkgrid')

# plot

fig, axes = plt.subplots(figsize=(6.18, 1.8), dpi=150)

axes.plot(x_lin, y_osc, label="Oscillations")

axes.legend()

axes.set_xlabel("Time (s)")

axes.set_ylabel("Oscillation (V)")

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Annotations¶

Pointing out particularities in graphs is sometimes helpful to explain or name observations on graphs. The following code block shows some options with self-explaining strings.

from matplotlib import rcParams

from matplotlib import rcParamsDefault

from matplotlib import style

rcParams.update(rcParamsDefault) # reset parameters in case you run this block multiple times

fig, axes = plt.subplots(figsize=(10, 2.5), dpi=150)

style.use('fivethirtyeight') # let s just use still another style

fig.suptitle('This is the figure (super) title', fontsize=8, fontweight='bold')

axes.set_title('This is the axes (sub) title', fontsize=8)

axes.text(1, 0.8, 'B-boxed italic text with axis coords 1, 0.8', style='italic', fontsize=8, bbox={'facecolor': 'green', 'alpha': 0.5, 'pad': 5})

axes.text(5, 0.6, r'Annotation text with equation: $u=U^2 + V^2$', fontsize=8)

axes.text(7, 0.2, 'Color text with axis coords (7, 0.2)', verticalalignment='bottom', horizontalalignment='left', color='red', fontsize=8)

axes.plot([0.5], [0.2], 'x', markersize=7, color='blue') #plot an arbitrary point

axes.annotate('Annotated point', xy=(0.5, 0.2), xytext=(2, 0.4), fontsize=8, arrowprops=dict(facecolor='blue', shrink=0.05))

axes.axis([0, 10, 0, 1]) # x_min, x_max, y_min, y_max

plt.show()

Challenge: The above code blocks involve many repetitive statements such as

import ...-rcParams.update(rcParamsDefault), andplot.show()at the end. Can you write a wrapper function to decorate a matplotlib plot function?

Exercise: Familiarize with built-in plot functions using matplotlib with the template scripts provided with the reservoir design and flood return period calculation exercises.

Plotting with pandas¶

Plotting with matplotlib can be daunting, not because the library is poorly documented (the complete opposite is the case), but because matplotlib is very extensive. pandas brings remedy with simplified commands for high-quality plots. The simplest way to plot a pandas data frame is pd.DataFrame.plot(x="col1", y="col2"). The following example illustrates this fundamentally simple usage with a river discharge series stored in a workbook (download example_flow_gauge.xlsx).

import pandas as pd

flow_df = pd.read_excel('data/example_flow_gauge.xlsx', sheet_name='Mean Monthly CMS')

print(flow_df.head(3))

flow_df.plot(x="Date (mmm-jj)", y="Flow (CMS)", kind='line')

pandas and matplotlib¶

Because pandas plot functionality roots in the matplotlib library, those can be easily combined, for example, to create subplots:

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from matplotlib import cm

flow_ex_df = pd.read_excel('data/example_flow_gauge.xlsx', sheet_name='FlowDuration')

fig, axes = plt.subplots(nrows=1, ncols=2, figsize=(10, 2.5), dpi=150)

flow_ex_df.plot(x="Relative exceedance", y="Flow (CMS)", kind='area', color='DarkBlue', grid=True, title="Blue area plot", ax=axes[0])

flow_ex_df.plot(x="Relative exceedance", y="Flow (CMS)", kind='scatter', color="DarkGreen", title="Green scatter", marker="x", ax=axes[1])

Boxplots and Error Bars¶

A box-plot graphically represents the distribution of (statistical) scatter and parameters of a data series.

Why use a box-plot with a pandas data frame? The reason is that with pandas data frames, we typically load data series with per-column statistical properties. For instance, if we run a steady-flow experiment in a hydraulic lab flume with ultrasonic probes for deriving water depths, we will observe signal fluctuation, even though the flow was steady. By loading the signal data into a pandas data frame, we can use a box plot to observe the average water depth and the noise in the measurement among different probes. Thus, probes with unexpected noise can be identified and repaired. This small example can be applied on a broader scale to many other sensors and for many other purposes (noise does not always mean that a sensor is broken). A box-plot has the following attributes:

- boxes represent the main body of the data with quartiles and confidence intervals around the median (if activated).

- medians are horizontal lines at the median (visually in the middle) of every box.

- whiskers are vertical lines that extend to the most extreme, non-outlier data points.

- caps are small horizontal line endings of whiskers.

- fliers are outlier points beyond whiskers.

- means are either points or lines of dataset means.

pandas data frames make use of matplotlib.pyplot.boxplot to generate box-plots with df.boxplot() or df.plot.box(). The following example features box-plots of water depth measurements with ultrasonic probes (sensors 1, 2, 3, and 5) stored in FlowDepth009.csv (download).

us_sensor_df = pd.read_csv("data/FlowDepth009.csv", index_col=0, usecols=[0, 1, 2, 3, 5])

print(us_sensor_df.head(2))

fig, axes = plt.subplots(nrows=1, ncols=2, figsize=(10, 2.5), dpi=150)

fontsize = 8.0

labels = ["S1", "S2", "S3", "S5"]

# make plot props dicts

diamond_fliers = dict(markerfacecolor='thistle', marker='D', markersize=2, linestyle=None)

square_fliers = dict(markerfacecolor='aquamarine', marker='+', markersize=3)

capprops = dict(color='deepskyblue', linestyle='-')

medianprops = {'color': 'purple', 'linewidth': 2}

boxprops = {'color': 'palevioletred', 'linestyle': '-'}

whiskerprops = {'color': 'darkcyan', 'linestyle': ':'}

us_sensor_df = us_sensor_df.rename(columns=dict(zip(list(us_sensor_df.columns), labels))) # rename for plot conciseness

us_sensor_df.boxplot(fontsize=fontsize, ax=axes[0], labels=labels, widths=0.25, flierprops=diamond_fliers,

capprops=capprops, medianprops=medianprops, boxprops=boxprops, whiskerprops=whiskerprops)

us_sensor_df.plot.box(color="tomato", vert=False, title="Hz. box-plot", flierprops=square_fliers,

whis=0.75, fontsize=fontsize, meanline=True, showmeans=True, ax=axes[1], labels=labels)

Box-plots represent the statistical assets of datasets, but box-plots can quickly become confusing (messy) when they are presented in technical reports for multiple measurement series. Yet, it is state-of-the-art and good practice to present uncertainties in datasets in scientific and non-scientific publications, but somewhat more easily than, for example, with box-plots. To this end, so-called error bars can be added to data bars. Error bars graphically express the uncertainty of a data set simply, by displaying only whiskers. Regardless of whether scatter or bar plot, error bars can easily be added to graphics through matplotlib (more in the developer's docs). The following example shows the application of error bars to bar plots of the above ultrasonic sensor data.

fig, axes = plt.subplots(nrows=1, ncols=2, figsize=(10, 2.5), dpi=150)

# calculate stats

means = us_sensor_df.mean()

errors = us_sensor_df.std()

# make error bar bar plots

means.plot.bar(yerr=errors, capsize=4, color='palegreen', title="Error bars", width=0.3, fontsize=fontsize, ax=axes[0])

means.plot.barh(xerr=errors, capsize=5, color="lightsteelblue", title="Horizontal error bars", fontsize=fontsize, ax=axes[1])

In scatter plots, errors are present in both x and y directions. For instance, the x-uncertainty may result from the measurement device precision, and y-uncertainty can be a result of signal processing. The above error measure in terms of the standard deviation is just an example of error amplitude. To measure and represent uncertainty correctly, always refer to device descriptions and assess precision effects of multiple devices or signal processing by calculating the propagation of errors.

More options for visualizing a pandas data frame is provided in the developer's visualization docs. Keep in mind that matplotlib can always be applied on top of a pandas plot.

Interactive Plots with plotly¶

The above shown matplotlib and pandas packages are great for creating static graphs in a desktop, report, or paper environment. Although interactive plots for web presentations can be created with matplotlib (read more in the matplotlib docs), the plotly library leverages many more interactive web plotting options within an easy-to-use API. plotly can also handle JSON-like data (hosted somewhere on the internet) to create web applications with Dash. Just one issue: the company behind (Plotly) is business-oriented...

Installation¶

plotly is not a default package neither in the flusstools environment file (environment.yml), nor in the conda base environment. Therefore, it must be installed manually with conda prompt (or Conda Navigator if you prefer the Desktop version). Therefore, for usage with Juypter, open conda prompt to install plotly for:

- jupyter usage and a conda environment:

conda install plotly(confirm installation when asked for it)

jupyter labextension install jupyterlab-plotly@4.11.0(change version4.11.0to latest version listed here)

optional:conda install -c plotly chart-studio(good for other plots than featured on this page) - jupyter usage in a virtual environment:

pip install plotly

For troubleshooting, visit the developer's website and fix problems with jupyter or Python (there may be some...).

To install plotly in flussenv (e.g., for usage with Juypter, PyCharm, or Atom) use either :

- a conda environment (recall installation instructions):

conda activate flussenvconda install plotly(confirm installation when asked for it)conda install "notebook>=5.3" "ipywidgets>=7.2"

- a pip environment (recall installation instructions):

source vflussenv/bin/activatepip install plotly

Read more about installing packages in a conda environment or pip environment.

Usage (Simple Plots)¶

plotly comes with datasets that can be queried online for showcases. The following example uses one of these datasets (find more at plotly.com).

Recall: If the graph is not showing up, open Anaconda Prompt and make sure to install support for Jupyter Notebook in the active environment:

conda install "notebook>=5.3" "ipywidgets>=7.2"

import plotly.express as px

import plotly.graph_objects as go

import plotly.offline as pyo

pyo.init_notebook_mode()

df = px.data.gapminder().query("continent=='Europe'")

fig = px.line(df, x="year", y="pop", color='country')

fig.show()

pyo.iplot(fig, filename='population')

In hydraulics, we often prefer to visualize data in locally stored text files, for example, after processing output from 2d-numerical modeling with NumPy or pandas. plotly works hand-in-hand with pandas and the following example features plotting pandas data frames, build from a csv file, with ploty (better solutions for pandas data frame sorting are shown in the pandas reshaping section). The following example uses plotly.offline to plot data in notebook mode (pyo.init_notebook_mode()) and pyo.iplot() can be used to write plot functions to a locally-living script for interactive plotting. The csv file comes from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) data center FAOSTAT (download temperature_change.csv).

import plotly.graph_objects as go

import plotly.offline as pyo

import pandas as pd

pyo.init_notebook_mode() # activate to create local function script

df = pd.read_csv("data/temperature_change.csv")

# filter dataframe by country and month

country_filter = "France" # available in the csv: Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany

month_filter1 = "January"

month_filter2 = "July"

df_country = df[df.Area == country_filter]

df_country_month1 = df[df.Months == month_filter1]

df_country_month2 = df[df.Months == month_filter2]

# define plot type = go.Bar

bar_plots = [go.Bar(x=df_country_month1["Year"], y=df_country_month1["Value"], name=str(month_filter1), marker=go.bar.Marker(color='#86DCEB')),

go.Bar(x=df_country_month2["Year"], y=df_country_month2["Value"], name=str(month_filter2), marker=go.bar.Marker(color='#EA9285'))]

# set layout

layout = go.Layout(title=go.layout.Title(text="Monthly average surface temperature deviation (ref. 1951-1980) in " + str(country_filter), x=0.5),

yaxis_title="Temperature (°C)")

fig = go.Figure(data=bar_plots, layout=layout)

# In local IDE use fig.show() - use iplot(fig) to procude local script for running figure functions

#fig.show(filename='basic-line2', include_plotlyjs=False, output_type='div')

pyo.iplot(fig, filename='temperature-evolution')

Interactive map applications¶

plotly uses the GeoJSON data format (an open standard for simple geospatial objects) in interactive maps. The developers provide many examples in their documentation and the below code block replicates a map representing unemployment rates in the United States. More examples are available at the developer's website.

import plotly.offline as pyo

from urllib.request import urlopen

import json

import pandas as pd

pyo.init_notebook_mode() # only necessary in jupyter

with urlopen('https://raw.githubusercontent.com/plotly/datasets/master/geojson-counties-fips.json') as response:

counties = json.load(response)

df = pd.read_csv("https://raw.githubusercontent.com/plotly/datasets/master/fips-unemp-16.csv", dtype={"fips": str})

import plotly.express as px

fig = px.choropleth_mapbox(df, geojson=counties, locations='fips', color='unemp',

color_continuous_scale="Viridis",

range_color=(0, 12),

mapbox_style="carto-positron",

zoom=2, center = {"lat": 35.0, "lon": -90.0},

opacity=0.5,

labels={'unemp':'Unemployment rate (%)'}

)

fig.update_layout(margin={"r":0,"t":0,"l":0,"b":0})

fig.show()

Many more maps are available - some of them require a Mapbox account and the creation of a public token (read more at plotly.com).