import numpy as np

import astropy.units as u

import astropy.constants as c

Maximum and Minimum orbital separations¶

In this lecture, we are going to discuss

- The minimum distance between 2 bodies before disruption occurs.

- The maximum separation between 2 bodies before a 3rd body is capable of disturbing the orbit.

Roche Limit¶

Given that tidal forces cause tidal bulges to appear in a body, then an obvious question that arises is:"are tidal forces ever strong enough to tear a body apart?". This is the key question that we will be covering in this next topic.

The condition for a body to be disrupted due to tidal forces is that the tidal acceleration must larger than the accelration due to self-gravity. Formally, this is given by: $$ a_{\rm tidal} > a_{\rm self-gravity} $$ The Roche limit is the smallest orbit which is stable against this effect.

Method 1¶

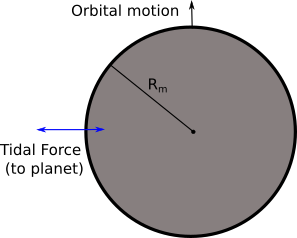

As a starting point, let's consider a small body of mass $m$ and radius $R_{\rm m}$, which is separated from some larger, stable body of mass $M$ by a distance $d$. We want to figure out when the tidal force experienced by the small body is large enough that its self-gravity cannot resist the pull of the larger body. We can substitute in for those accelration terms using the expressions for $F_{\rm tidal}$ and $F_{\rm self-gravity}$. This gives $$ \frac{2GMR_{\rm m}}{d^3} > \frac{G m}{R_{\rm m}^2} $$ For this, we find that $$ d<\left(\frac{2M}{m}\right) ^{1/3} R_{\rm m} $$ So if the separation is less than this value, then the orbiting body will be torn asunder. We can rewrite this in terms of densities also (which is more convient in particular examples). From here on out, we're going to assume a Planet-Moon system, and we'll use P for Planet and m for moon. The densities of these bodies is given by $$ M_{\rm P} = \rho _{\rm p} \frac{4}{3} \pi R_{\rm P}^3, \: \; \; m_{\rm m} = \rho _{\rm m} \frac{4}{3} \pi R_{\rm m}^3 $$ and so $$ \frac{2M}{m} = 2 \frac{\rho _{\rm P} R_{\rm P}^3}{\rho _{\rm m} R_{\rm m}^3} $$ giving us $$ d< 2^{1/3} \left( \frac{\rho _{\rm P}}{\rho _{\rm m}}\right) ^{1/3} R_{\rm p}. $$

Method 2¶

Ok, the above was a very simplified way of looking at this. Let's try make it more complicated and include centripetal acceleration due to orbital motion. Consider a mass element on the side of the orbiting moon facing the planet (as below).

In this case, we need to ask the question "when is the gravitational acceleration felt by the mass element larger than the centripetal acceleration?" $$ \frac{G M}{(d-R_{\rm m})^2} - \frac{Gm}{R_{\rm m}^2} > \omega^2(d-R_{\rm m}) $$ where $\omega$ is the angular velocity of the moon, and is given by: $$ m \omega^2 d = \frac{GMm}{d^2} $$ $$ \omega^2 = \frac{GM}{d^3} $$ Using this expression the Roche Limit condition becomes $$ \frac{G M}{d^2} \left( 1-\frac{R_{\rm m}}{d} \right)^{-2} - \frac{Gm}{R_{\rm m}^2} > \frac{GM}{d^3}(d-R_{\rm m}) $$ which simplifies to (ssuming $R_{\rm m}<<d$) $$ d < 3^{1/3} \left(\frac{M}{m}\right)^{1/3}R_{\rm m} $$ $$ d < 3^{1/3} \left( \frac{\rho _{\rm P}}{\rho _{\rm m}}\right) ^{1/3} R_{\rm p}. $$ which is very similar to what we derived with our simple approximation - the only difference is the leading constant, which is $2^{1/3}=1.26$ in the simplest case, and $3^{1/3}=1.44$ when we account for centripetal force.

Method 3¶

Derived by Roche in 1850, where he assumed the bodies were "fluid, prolate spheroids" (so similar to a rugby ball), and got the same dependance as above, but with a constant of 2.45. For actual problems, this coefficient is what should be used.

Example: Saturns rings¶

The average density of Saturn is 710 kg/m$^3$, its radius is $6.03\times 10^7$ m. The moon Titan has a density of 1880 kg/m$^3$. The Roche limit for a moon with Titan's density (and using the coefficient of 2.45) is $$ d_{\rm min} = 2.45 \left( \frac{\rho _{\rm Saturn}}{\rho _{\rm Titan}}\right) ^{1/3} R_{\rm Saturn} $$ $$ d_{\rm min} = 107,000 \: {\rm km} $$ Since Titan exists, and has not been disrupted, we would expect it to lie outside this distance. Indeed, Titan's actual distance from Saturn is $1.22\times10^6$ km.

But what about Saturn's rings? They extend from 88,000 km to 136,000 km, while all major moons are located oustide this distance. This suggests that the rings may be from a moon whose density was similar to Titan, which was then tidally disrupted.

rho_sat = 710*u.kg/u.m**3

R_sat = 6.03e7*u.m

rho_titan = 1880*u.kg/u.m**3

a_min = 2.45*(rho_sat/rho_titan)**(1/3)*(R_sat)

print(a_min.to(u.km))

106786.63373076545 km

Example: Phobos¶

Phobos, Mars moon, has a density of $\rho=1900$ kg m$^{-3}$, while Mars has a density of $\rho=3900$ kg m$^{-3}$ and a radius of $3397$ km. The Roche limit is thus $$ d_{\rm min} = 2.45 \left( \frac{\rho _{\rm Mars}}{\rho _{\rm Phobos}}\right) ^{1/3} R_{\rm Mars} $$ $$ d_{\rm min} = 10,600 \: {\rm km}. $$ And yet, the semimajor axis of Phobos' orbit is 9400 km - so it lies within the Roche limit. Why hasn't it been tidally disrupted? (Consider the caveats of what we've discussed above, mainly what forces we have included and neglected).

rho_mars = 3900*u.kg/u.m**3

R_mars = 3397*u.km

rho_phobos = 1900*u.kg/u.m**3

a_min = 2.45*(rho_mars/rho_phobos)**(1/3)*(R_mars)

print(a_min.to(u.km))

10577.068084828958 km

Hill Radius/Instability Limit¶

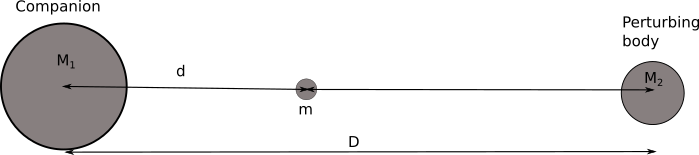

If an orbiting body is too far away from its companion, perturbations due to the other bodies can become important, causing the body to escape if the distance exceeds the instability limit. Consider the setup below.

The escape condition for $m$ is $$ \frac{GM_2}{(D-d)^2}-\frac{GM_2}{D^2} > \frac{G M_1}{d^2} $$ You can think of this as a tug of war. On the left, we have the acceleration felt by orbiting body ($m$) and the primary mass ($M_1$) feel due to the perburing body ($M_2$), and on the right we have the gravitational accleration the orbiting body feels towards the primary. Doing some rearranging, and assuming $d<<D$, we get $$ \frac{M_2}{D^2} (1+\frac{2d}{D})-\frac{M_2}{D^2} > \frac{M_1}{d^2} $$ $$ d > \left(\frac{M_1}{2M_2}\right)^{1/3}D $$

Example: Sun, Moon, Earth system¶

Ok, let's set this example up as: $M_1=M_{\oplus}=5.97\times10^{24}$ kg, $M_2=M_{\odot}=2\times10^{30}$ kg, $D=1$ AU. We get

$$ d > \left(\frac{M_\oplus}{2M_\odot}\right)^{1/3} D $$$$ d > 1.71\times10^9 \; {\rm m} $$The actual distance between the Earth and the Moon is $3.84\times10^8$m, which is 0.22$d$. So the moon is stable against the perturbing effect of the Sun!

M1 = 1*c.M_earth

M2 = 1*u.solMass

D = 1*u.au

d_min = (M1/(2*M2))**(1/3)*(D)

print("Instability limit is d>{:e}".format(d_min.to(u.m)))

Instability limit is d>1.713132e+09 m